The Making of Black History Month in the USA

In 1926, a historian with a radical conviction quietly set in motion a cultural intervention that has helped to define and elevate Black history. Dr. Carter G. Woodson, an American historian, author, and journalist and called the “Father of Black history” believed that knowing your history, being aware of the impact and contributions of Black people was power. And he understood that if Black people were absent from the historical record, they would remain marginalised in the present. That year, through the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, he launched Negro History Week.

One hundred years later, February 2026 marks the centenary of that moment, a week that grew into what we now know as Black History Month in America.

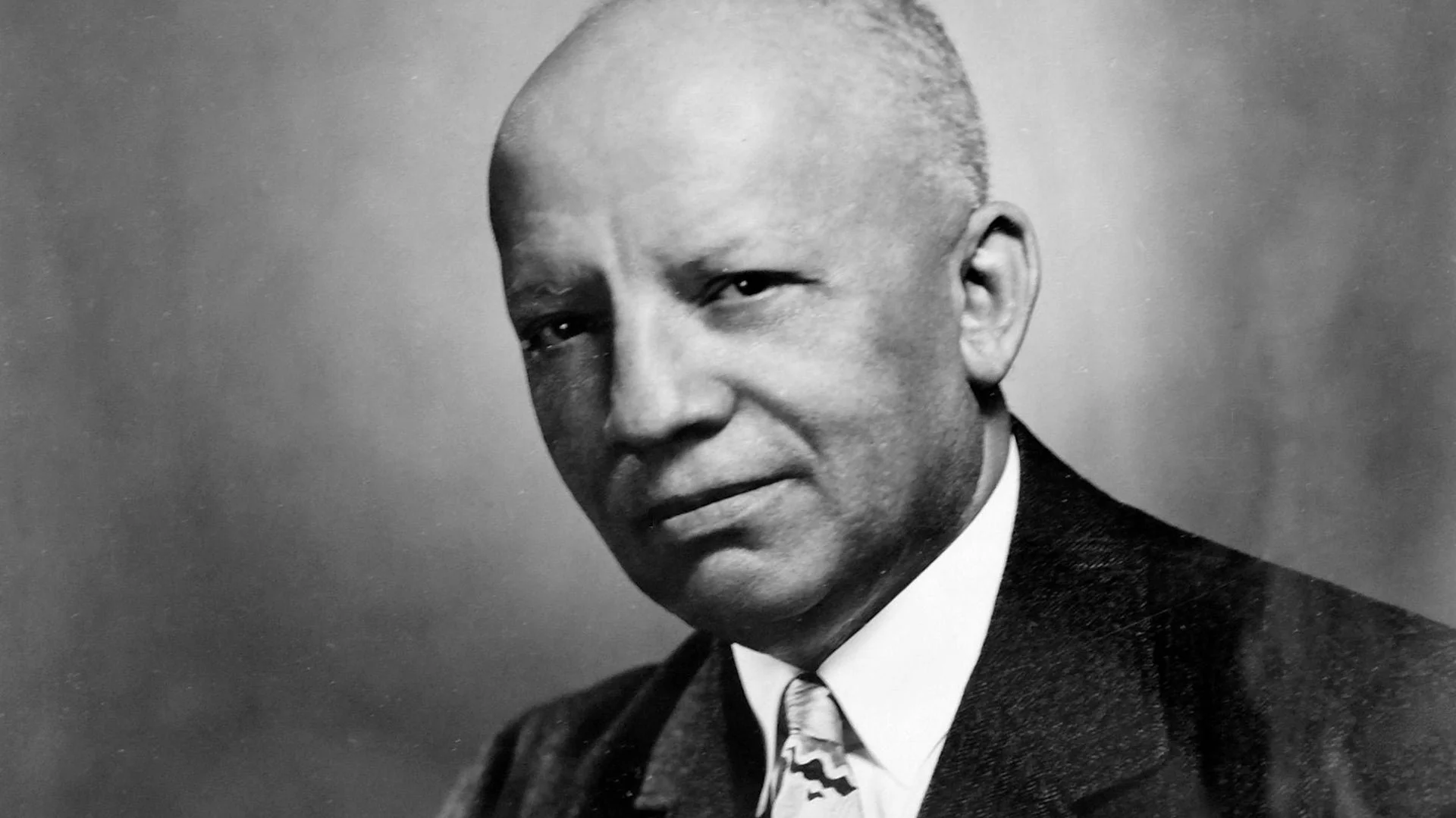

Dr. Carter G. Woodson

Dr.Carter G. Woodson (1875–1950)

Woodson was born in Virginia to formerly enslaved parents, he worked in coal mines before pursuing higher education, eventually earning a PhD from Harvard University in 1912, becoming the second African American after W. E. B. Du Bois to do so, and the only person whose parents had been enslaved to earn a PhD in history. Excluded from much of the white-dominated historical profession, Woodson founded the Association for the Study of African American Life and History in 1915 to promote rigorous research into Black life and history.

Why celebrate Black History Month in February?

Woodson chose February deliberately to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, dates already recognised within Black communities. Woodson knew that the appeal would be greater having it anchored by the celebration of figures associated with emancipation and Black freedom, while also expanding the narrative beyond those two men to include the wider African diaspora. The goal was not token celebration, but educational transformation: encouraging schools, churches and civic groups to teach Black history with academic rigour.

From Negro History Week to Black History Month

The idea spread quickly through schools, churches and community organisations. By the 1960s, amid civil rights struggles and the rise of Black consciousness movements, a week no longer felt sufficient. In 1976, during the United States Bicentennial, President Gerald Ford formally recognised Black History Month, expanding the observance to February in its entirety. What began as an academic campaign became a national institution, and eventually, a global one.

Over the decades, the narrative has expanded. Early commemorations often centred on enslavement and emancipation. Later decades widened the lens to include resistance movements, artistic revolutions, scientific breakthroughs, entrepreneurship and cultural innovation. Black history shifted from being framed solely through oppression to being understood as a story of brilliance, endurance and global influence.

The observance has not been confined to the United States. In the United Kingdom, Black History Month takes place in October, shaped in part by the work of activists such as Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, a Ghanaian analyst, journalist and pan-African activist who helped establish it nationally in 1987. British commemorations often centre Windrush histories, African and Caribbean migration, and the political and cultural contributions of Black Britons, narratives historically sidelined in national discourse. Canada also formally recognises Black History Month in February, while countries across Europe, including Ireland and Germany, have developed their own observances.